Leafhoppers belong to Hemiptera: Cicadellidae and one of the most well-studied species is the potato leafhopper, Empoasca fabae Harris. It has been proven (1,2) that these insects are long-range migrants, and tend to colonize an area based on surface airflow convection currents and high and low pressure fronts. Because they can be significant agricultural pests (alfalfa, clover, beans, tomato, potato, hops, maple, apple), it is important to understand the factors that contribute to their abundance…

Continue readingCategory Archives: invasives

Japanese beetle info

I mentioned in last week’s newsletter that the Oregon Dept of Agriculture (ODA), Washington State Dept of Agriculture (WSDA), and Washington State University (WSU) are all active in their efforts to prevent and detect Japanese beetles in the region. Remember:

- This Thursday, April 1st, at 9am, WSU/WSDA is offering a webinar. Click here to register and learn more.

Also be sure to check out the OSU Extension publication that includes information on identification, life cycle and scouting, damage, control measures, and how to report a suspected Japanese beetle. EM 9158 Published April 2017 4 pages https://catalog.extension.oregonstate.edu/em9158

Northern Giant Hornet – PNW info sources

QUICK FACTS

- There are many black and yellow wasps in Oregon. Proper identification is important before reporting. Here are some ID tips:

- This wasp is very LARGE! 1.5″ to 2″ long

- It has a striped abdomen, yellow head, and black eyes

- The thorax (where wings attach) is black

- Predator of many large-bodied insects (grasshoppers, beetles, etc.)

- Potential serious threat to honeybees

- Ground-nesting, active from May to August

- Detected in August 2019 British Columbia (eradicated); 0 confirmed sightings to date in Oregon. 4 confirmed sightings (dead) in Washington state + 1 active nest – read news articles from October 2020;

OTHER REGIONAL RESOURCES

There are a number of regional experts who can offer advice, answer questions, and field suspected reports of sightings. Please consult the OSU Extension publication for ID tips, answers to common questions, etc. Early detection is key to limit the effects of invasive species.

- Ask-an-Expert – Featured question from homeowner, answered by OSU faculty (AUG 2022)

- Read this Pest Alert – from the Oregon Invasive Species Council (APR 2020)

- Watch this webinar – by WSDA Entomologist Chris Looney in partnership with the Washington Invasive Species Council (FEB 2020).

- Report a sighting in Oregon

- Report a sighting in Washington

- View this factsheet from ODA’s Insect Pest Prevention and Management program (.pdf, updated MAY 2020)

- Read this opinion by a Distinguished CSU Professor about why ‘murder hornet’ is an unfair name for a generalist predator.

“It is certainly something to be … watchful for … [but]… I don’t think there’s a need for panic at all” ~ Eric Lee-Mader

Lee-Mader is a pollination conservation expert with the Xerces Society and has worked with AGH in Japan. Quotes extracted from his 4 MAY 2020 interview with KGW8 News, available here.

The day the boat turned white: a tale of leafhopper migration

This is a summary of an article published in the Winter 2020 issue of the Oregon Small Farm News. The article was written by Dr. Toshihiko Nishio and translated and edited by Shinji Kawai and Abigail Hunter, OSU Dept. of Horticulture. The article is available as a .pdf by using the link below.

In 1967, an ocean vessel was in the East China Sea conducting standard atmospheric and marine environment monitoring when, all of a sudden…

Tens of thousands of small insects surrounded the vessel, like powdery snowflakes

Dr. T. NiSHio, rice farming system researcher

Little did the ship’s crew know – that experience would help scientists learn more about a very serious pest problem in rice. In fact, rapid invasions of planthoppers is thought to be one of the major causes of historical famines in Japan.

Ryoichi Kishimoto, who worked at a local agricultural research station formed a group to intensively study the planthoppers. They set up light traps, pan traps, and even windsocks to monitor at different locations throughout the region. In 1971, Kishimoto published his theory about long-range migratory patterns of the pest, which ignited international interest.

20 years after the original observation, another researcher from the same experiment station proved that the planthopper’s migration corridor includes a low-level jetstream from southern China to western Japan. This is how they are able to travel such massive distances in just a few days, and why they would’ve been observed by the ocean vessel.

Learn More

- http://www.naro.affrc.go.jp/english/laboratory/karc/

- Liu, T., Wang, B., Hirose, N. et al. High-resolution modeling of the Kuroshio current power south of Japan. J. Ocean Eng. Mar. Energy 4, 37–55 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40722-017-0103-9

- Observations by Japanese Meteorological research vessels are still available today!: https://www.data.jma.go.jp/gmd/kaiyou/db/vessel_obs/data-report/html/ship/ship_e.php

- Hu G. et al. Outbreaks of the Brown Planthopper Nilaparvata lugens (Stål) in the Yangtze River Delta: Immigration or Local Reproduction? PLOS ONE 9 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0088973

- Chapman, J. W. et al. Long-range seasonal migration in insects: mechanisms, evolutionary drivers and ecological consequences. Ecology Letters 18 pp: 287-302 (2015).

Wireworms in W.OR?

(Coleoptera: Elateridae) Agriotes spp.

Adults = click beetles; Larvae = wireworms

Spring is a critical time to assess wireworm populations because when soil temperatures warm to 50°F, larvae begin to migrate up within the soil column and seek underground plant tissues to feed on. Root crops are most commonly damaged, but chewing on seeds, seedlings, and fruit also have been reported.

I am coordinating a pitfall trapping effort to determine if non-native adult click beetle species are present in western Oregon (contact me if you’d like to participate). To monitor your own fields, bait stations are recommended, because they are a better indicator of actual, larval (wireworm) pressure.

I will post a more detailed pest profile page in the coming weeks, but for now:

For more information, click the link to read a publication by Nick Andrews et. al re: Biology and Nonchemical Mgmt. in PNW potatoes.

2-may-19 update: the PEST PROFILE PAGE is ready, and has more details about how to monitor, ID, etc.

BMSB in Veg Crops

Tis’ the Season! According to a pest model for this region, the summer generation of brown marmorated stink bug (BMSB) adults start appearing this week. This pest is very mobile, and will move into fall crops readily. I caught a glimpse of an egg mass in sweet corn today (photo below), and nymphs are expected to peak within the next few days.

Bell pepper, sweet corn, and tomato are all considered desirable hosts. Symptoms include sunken kernels, whitening on fruits, and spongy tissue. Rather than re-invent the wheel, I decided to direct you to some GREAT resources (see list below) for BMSB ID and management in vegetables.

FOR MORE INFO:

Wiman lab page – Oregon State University – Identification, monitoring efforts, and resource list

Neilsen et al., 2008 – Rutgers University – Developmental details

BMSB info for vegetable growers – great photos of injury, explanation of life cycle, etc.

Western Corn Rootworm

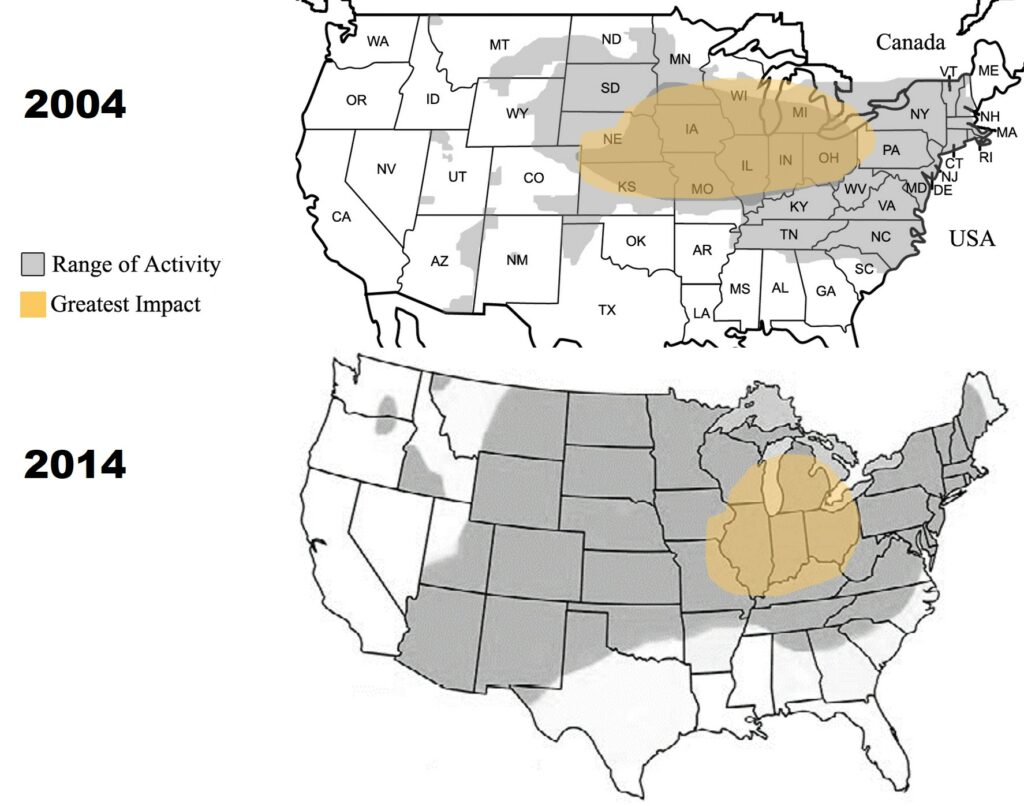

Western Corn Rootworm (WCR) is considered the most important corn pest in the U.S.1 . Most of this damage occurs in the Midwest, where corn acreage dominates the landscape. Over the last 50 years, farmers have used cultural, genetic, and chemical control strategies to lessen the effect of WCR and protect yields.

In comparison, the PNW produces a very small amount of corn (<5% of all regional farmland). Therefore, western corn rootworm has not been a problem for us so far2, and growers are much more accustomed to 12-spots (which is a western variant of the southern corn rootworm – confused yet?!)

Regardless of the species, rootworm damage is similar: larvae chew on roots, which can cause lodging or goosenecking. Adult beetles attack foliage and can clip silk (corn) or chew on blooms (squash) or pods (beans) if populations are high enough.

Q: So why mention WCR if it’s not yet a problem here?

A: This species is worth monitoring because it has been moving westward for the past 10+ years, and could become more abundant if corn production increases in the PNW. Yellow sticky traps are great passive sampling tools for many pests, so in short…might as well.

Also, the Oregon Dept. of Agriculture (ODA) asked us to conduct a preliminary distribution survey of D. D. virgifera in the PNW, both in field corn and sweet corn. You can read more about that project here: http://bit.ly/CRWinOR

RESOURCES:

- Gray, M. E., Sappington, T. W., Miller, N. J., Moeser, J., & Bohn, M. O. (2009). Adaptation and invasiveness of western corn rootworm: Intensifying research on a worsening pest. Annual Review of Entomology 54: 303-321.

- Murphy, A., Rondon, S., Wohleb, C., and S. Hines. (2014). Western corn rootworm in eastern Oregon, Idaho, and eastern Washington. PNW Extension Publication 662. 7 pp.

Pest Report – Week of July 24th

WEEK 16 – Two types of rootworm are now widely present in the Valley. See this page to learn how to ID and differentiate between them. Another, third species, may be on its way. Western corn rootworm has been moving westward since 2004.

Read the full report here: http://bit.ly/VNweek16 and subscribe on our homepage to receive weekly newsletters during field season. Thanks!