This post was originally published September 2, 2021. Posts have been manually reordered for more logical storytelling. To go to the next post in the sequence, click “Previous Post” at bottom.

Just a few short decades ago, in the mid-1970s, the number of recognized species of whales, dolphins, and porpoises worldwide was 76. Today, there are 93. Some are so poorly known that they have never been identified alive in the wild (they are known only from stranded specimens). All of these belong to a single genus of beaked whale: Mesoplodon.

Ginkgo-toothed beaked whale (scientific name: Mesoplodon ginkgodens). This is one of several species of beaked whale that has never been identified alive in the wild, known only from strandings on the beach (this photo was taken in New Zealand). Its description as a new species was based on measurements and associated data from the dead animal. Photo credit: New Zealand Department of Conservation.

Currently, there are 16 known species of Mesoplodon — including five added since the mid-1970s. Six of these have never been identified alive in the sea: M. perrini, M. hotaula, M. hectori, M. traversi, M. bowdoini, and M. ginkgodens — and one or more could live in Oregon waters. Although small by whale standards (4–6.2 m), mesoplodonts can still weigh well over one ton (900 kg), placing them among the largest 0.001% of animals on Earth.

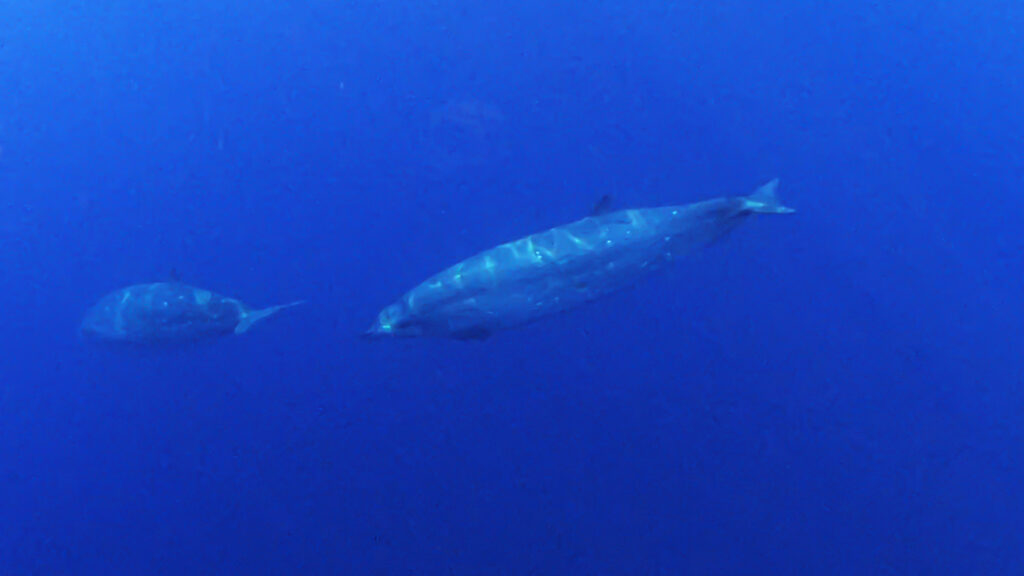

In 2014, during a research trip investigating the Eastern Garbage Patch (EGP, roughly halfway from Oregon to Hawaii), marine biologists photographed two separate groups of small, unidentified whales. Adult male mesoplodonts have species-specific dentition (a pair of erupted teeth that they use as tusks to vie for females), and the whales in the photographs appeared to be either M. ginkgodens, M. hotaula, or possibly a new species.

In September 2021, scientists from the Oregon State University’s Marine Mammal Institute (MMI) and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) are mounting a month-long expedition on the R/V Pacific Storm to search for this cryptic whale. Among the accumulated plastic debris and abandoned fishing gear of the EGP, they hope to find one of the largest, least known animals on the planet.

But why does this matter?

Human enterprise has made the ocean an extremely noisy place, from seismic testing used for science and oil exploration, to military use of high-intensity sonar to detect submarines. These sound sources have resulted in the deaths of untold numbers of beaked whales, apparently because a fright response causes individuals in deep water to bolt to the surface, which can result in bends-like symptoms and death.

Currently, mesoplodont beaked whales are among the least known whales in the world — we know very little about their numbers and distributions, or even how many species there are. The ability to identify them to the species level using their recorded acoustic signals could make it possible to survey these elusive animals using passive acoustic methods. That could be accomplished, for example, by attaching hydrophones and recorders to commercial vessels traveling across oceans within shipping lane “highways.”

This Gyre Expedition hopes to provide essential information to better understand the population status of beaked whales around the world and to assess their vulnerabilities to anthropogenic (human-caused) sounds.

This photograph was taken by a fisherman off the coast of Baja California, Mexico. The species is unknown. It is either one of the beaked whales that are known only from the description based on a dead animal found on the beach or a species new to science.

The Beaked Whale Expedition to the Eastern Pacific Gyre is a collaboration among Oregon State University’s Marine Mammal Institute, NOAA Southwest Fisheries Science Center’s Marine Mammal and Turtle Division, and NOAA Northeast Fisheries Science Center’s Protected Species Branch. It is made possible with seed funding from the MMI gray whale license plate program. The expedition is led by Principal Investigator Lisa T. Ballance (MMI), co-PI Robert Pitman (MMI), co-PI Jay Barlow (NOAA), and MMI collaborators Scott Baker, Daniel Palacios, and Leigh Torres.