(This post was originally published September 30, 2021. Posts have been manually reordered for more logical storytelling. To go to the next post in the sequence, click “Previous Post” at bottom.)

Part of the reason so little is known about the 23 recognized species of beaked whales is because they are so skittish at the surface. Vessels rarely approach within a few hundred meters before the whales slip under the waves, never to be seen again. Depending on the species, individual beaked whales can weigh anywhere from 1 to 12 tons, leaving them with seemingly little to fear in the ocean, but killer whales are nevertheless known to prey on them. Not surprisingly, beaked whales have evolved various behaviors that help them minimize contact with killer whales.

As deep divers — some to almost 3000 meters — beaked whales use echolocation to detect their prey (mainly squid and fish). Although beaked whales can out-dive them, killer whales have the benefit of superior hearing abilities. Consequently, when beaked whales surface to breathe, they quit vocalizing several minutes and several hundred meters below the surface. Then instead of coming straight up, they veer off in random directions to avoid detection by eavesdropping killer whales. At the surface, the beaked whales take a few quick gulps of air and then descend to several hundred meters for 10 minutes or more, before surfacing again. They do a series of these relatively shallow breathing dives before they make their deep foraging dive — the less time they spend at the surface and the less noise they make there, the less likely they are to attract bad company.

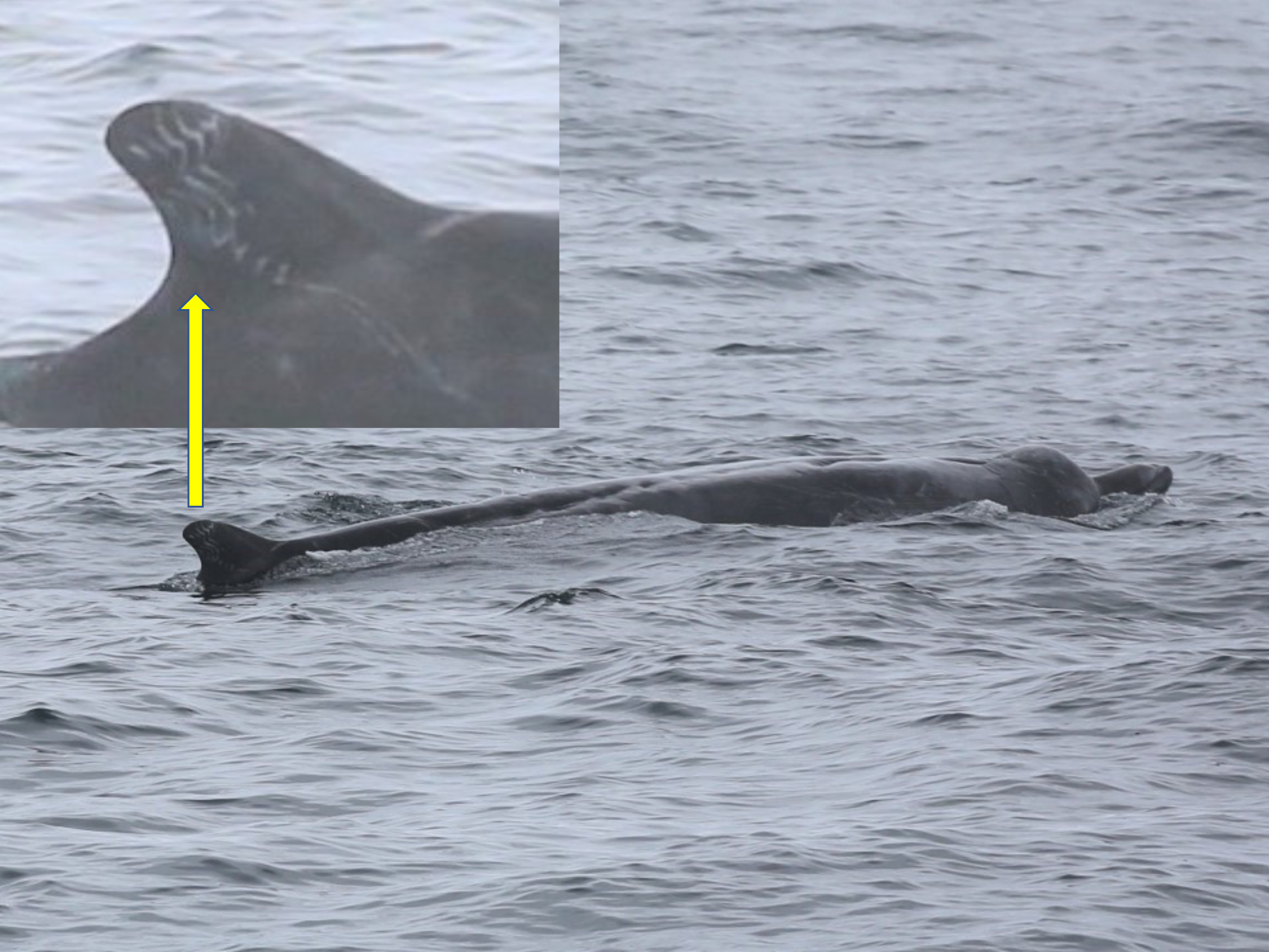

Beaked whales also have some physical features that make them harder to capture. Their pectoral flippers tuck into “pockets,” making them flush with the body and difficult for a killer whale to bite onto. The dorsal fin, instead of being mid-body like fast-swimming dolphins, is positioned back toward the flukes so that when the tail is pumping up and down, it is also going to be very difficult for a killer whale to grab ahold of.

At 35 feet in length, Baird’s beaked whale (Berardius bairdii) is the largest species of beaked whale, but it is still vulnerable to attacks by packs of killer whales. The photo above shows one of the Baird’s beaked whales that we encountered near Heceta Bank, Oregon; the enlargement reveals tooth rake scars on its dorsal fin left by an attacking killer whale. This whale got away, but Baird’s beaked whales often have killer whale tooth rake marks on them, and it can be assumed that others aren’t so lucky. Little wonder they are wary of their time spent at the surface.

~Bob Pitman