Streamflows, algae and aquatic plants, and invertebrate animals drive water quality and fish disease dynamics in the Klamath River, but gaps exist in our understanding on how they are all linked. The dam removals presented an opportunity to collect unique data on how these processes are connected. The ecology team is researching relationships between water quality, fish disease risk, and the aquatic plants and animals (worms!) that influence them. Results are relevant to a variety of landscape-scale changes that impacts streamflows, temperatures, and sediment and nutrients loads, including future dam removals, wildfires, and flow management.

These components also directly link to concepts of river health that are being examined with the Community Experiences and Knowledge Co-Production components of the project.

Algae and Rooted Aquatic Plants

Algae and aquatic plants provide the basis for aquatic food webs, influence water quality, and control carbon cycling in rivers. Despite the importance of algae and plants to freshwater ecosystems, increased growth and accumulation of algae, cyanobacteria, and aquatic plants beyond historic levels is a growing problem in rivers. Excess growth of algae and aquatic plants in the Klamath River impedes tribal fishing practices, restricts river access, and causes extreme fluctuations in dissolved oxygen and pH.

We are documenting growth and accumulation of algal and aquatic plants before and after dam removal and investigating their seasonal growth to understand how environmental changes caused by dam removal affect algae and aquatic plants. These changes are summarized in the diagram below, which illustrates the hypotheses we had about changing streamflows and sediment on plants and algae.

Evaluating these hypotheses involves high-frequency sampling of the plants and algae over the growing season. The data are also being analyzed to examine how production by the plants and algae has responded to changes in sediment concentrations, nutrients, and peak flows. Production is a measure of how fast and how much the plants and algae grow in the river and it is important because the plants and algae can control several aspects of water quality in the river, including pH and dissolved oxygen. Those data will be used to develop a new food-web model that will be used to simulate a range of potential management actions (changing peak flows, sediment loads, etc.).

2025 update

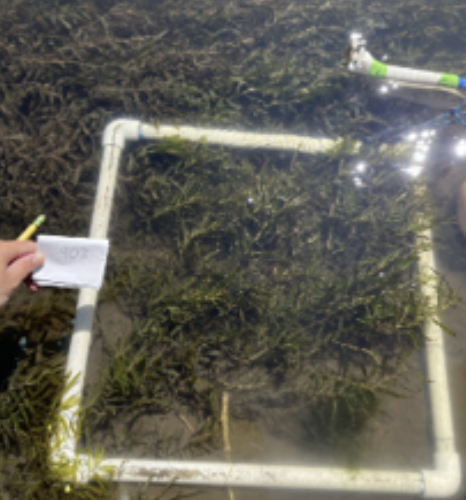

During the summer of 2025, we conducted field studies to document plant and algae datasets. At the Tree of Heaven site, we conducted bi-weekly field surveys to identify the conditions that best support the growth of algae and rooted aquatic plants. The number of field sites was reduced from two to one this year due to the frozen budget during winter/spring 2025. We also surveyed six reaches between Iron Gate Dam and Happy Camp, one time each during peak biomass conditions using similar techniques to the bi-weekly surveys at Tree of Heaven.

We surveyed for filamentous algae and rooted aquatic plants to compare biomass across a longitudinal gradient to a longer-term dataset (2019-2025) collected prior to dam removal. Year three of the plant and algae data collection provided further evidence regarding the primary importance of winter peaks flows to macrophyte growth, relative to a secondary driver of sediment concentration that drives light availability. This contradicted our original hypotheses that light was the primary control on aquatic plant and algal biomass during the year of dam removal. While comparison of longitudinal survey data between post- and pre-dam removal showed lower biomass of plants and algae in summer 2025 than in the pre-dam removal drought years, biomass was similar to a pre-dam removal year that had high winter flows before the growing season. The longitudinal surveys that include a longer time series (but no seasonal patterns) support the idea that winter flows may be as important for controlling biomass as summer water clarity. Results were presented at a number of venues listed on the Presentations page. We also continued to work with 2022-2023 field data and resulting models to finalize a manuscript for submission.

2024 update

In our year 2 of field surveys, we sampled two sites downstream of Iron Gate Dam over this summer 2024 during dam removal, with each survey taking place bi-weekly from June through August. At each site we measured ~80 different locations (quads) throughout the site each time we surveyed.

At our upriver site, Tree of Heaven Campground, plants were already well established at the beginning of the summer despite the muddy, turbid river. The lack of spring peak flows seemed to have helped them overwinter and suggesting that peak flows may be more important than abundant light availability at the start of summer.

At our downriver site, Big Bar, we observed little to no growth at the beginning of the summer. The tributaries between the two sites add a lot of water to the river, and peak flows in the lower river were elevated this year. This annecdotally reinforces the importance of peak flows.

At both sites, continuous high turbidity later in the summer seemed to result in algae decaying and dying off as water levels also dropped and the river contracted, as was observed by dried algae along the dried out banks.

Source: OSU Media

Salmon parasites

The myxozoan parasite Ceratonova shasta (C.shasta) causes mortality (up to 90% in some years) in outmigrating juvenile salmon. The parasite alternately infects annelid (worm) and salmon hosts in order to complete its life cycle. The annelid hosts release the (short-lived) parasite stage that infects the salmon so understanding the factors that drive the distribution and density of infected annelids is central to managing of disease risk in juvenile and adult salmon. This study informs our knowledge of annelid host ecology by describing diets of the suspension feeding annelids, and how reservoir removal and subsequent changes in the algae and aquatic plants in the river in turn affect annelid host density or distribution.

2025 update

Aquatic worms that were sampled from sites across the basin in March, May, July and October 2025 (sampling funded by USBR contract BOR/USGS Interagency Agreement #R23PG00059) were slide mounted for gut contents and size structure analyses and data collection is underway. Analytical approaches for examining relationships between worm population and individual success (body condition, gut contents), infection (prevalence, density of infected worms) and water quality metrics were discussed and revised. Annelids were slide mounted (n>30 per site) from sites representing low, intermediate, and high flow related disturbance, and water years representing dry (2015, 2021), wet (2017, 2019) and post-dam removal (subset 2024, all 2025) during juvenile salmon outmigration season (spring; co-occurrent with seasonal risk of C. shasta infection). All samples have been processed for gut contents and body size and condition. Preliminary analyses (Figure 2) indicate that pre-dam removals, annelid hosts reproduced earlier, evidenced by a smaller mean body length and larger confidence intervals which indicate juvenile recruitment, at lower disturbance sites and in dry years. In contrast, mean annelid body length is greater in spring at high disturbance sites and in wet water years. This result is explained by the distribution of adults and lack of juvenile annelids under these conditions. Notably, post dam removal annelid body length data are most similar to those of wet water years across the disturbance gradient (Figure Annelid results, a). Preliminary data from gut contents analyses indicate median sediment grain sizes are comparable in annelid hosts from sites across the range of the disturbance gradient in dry years, and that larger grain sizes are observed in annelids in wet and post dam removal years, likely reflecting a lack of availability of smaller (preferred; smaller sediment grains have larger relative surface areas for bacteria) grain sizes (b). In addition, mean diatom counts in annelid gut contents were high in annelid hosts in dry water years, and low in wet and post-dam removal years (c). This result may be explained by delays in the onset of ‘green up’ in the latter water years, and the differences would likely level out by summer.

2024 update

Salmonid risk of C. shasta in 2024 was elevated downstream from Iron Gate dam during juvenile outmigration season, and annelid host densities (preliminary) in this reach were high in winter and spring but declined in summer and fall. Proposed mechanism to explain decline is 1) composition of suspended sediments and 2) deposition of fine sediments/burial.

- Preliminary models built describing relationships between water quality variables and annelid variables have been built using data collected 2021-2023.

- Characterization of annelid gut contents in annelids from infectious zone is ongoing, but preliminary data show there are differences in composition of gut contents in 2024 relative to pre-dam.

Dissolved Oxygen

Dissolved oxygen is necessary for the survival of fish and other wildlife in rivers. In the Klamath River, the amount of dissolved oxygen can be affected my several environmental factors, such as temperature, primary production, turbulence, and sediment pulses.

During sediment pulses, large quantities of sand, silt, clay, and organic matter (like dead plants or algae) can get pushed through the river by landslides, fires, heavy rain, or the removal of dams. These sediment pulses can block sunlight from reaching the riverbed, inhibiting photosynthesis and affecting the amount of oxygen being produced in the river. Additionally, sediment pulses contain organic matter, such as plant and algae particles. These particles attract microorganisms, such as bacteria, that decompose the organic matter. These microorganisms breathe in oxygen just like us, and can consume significant quantities of oxygen from the river.

When the dam is removed, the sediment currently trapped behind the dam will be flushed into the river, and will remain the river for up to one year. This part of the study aims to quantify the amount of dissolved oxygen consumed by the sediment pulse and model the recovery of dissolved oxygen as the sediment pulse makes its way out of the Klamath River.

2025 update

Dissolved oxygen experienced 4 measured drops during reservoir drawdown – only two drops to levels considered lethal for most fish (<5 mg/L). Dissolved oxygen levels reached 0 mg/L two separate times on the order of hours for up to 35 – 60 miles downstream of the dams. The remaining two dissolved oxygen events were mild, and levels remained above the lethal threshold.

Dissolved oxygen appears to be closely correlated with particulate organic matter, and closed incubation data suggest that at least two mechanisms were consuming dissolved oxygen in the river at two different time scales during sediment pulses.

2024 update

Between January and May 2024, we sampled three sites downstream of the former Iron Gate Dam to the confluence with the Shasta River. Field work involved collecting samples of water and sediment to bring back to the lab, making measurements of water quality parameters and velocity, and babysitting some sensors that we left in the river to continuously measure dissolved oxygen and temperature.

During that period, there were four occurrences during which dissolved oxygen dropped during reservoir drawdown. Two of these drops were to levels considered lethal for most fish species. Evidence suggests that these drops were caused by multiple mechanisms, including biological oxygen demand from the organic matter stored in the reservoir bed sediment, chemical oxygen demand from the reduced minerals in the sediment, and anoxic (no-oxygen) water present just above the sediment bed in the former reservoir. Data analysis is underway!

Meet the Ecology Team

Desiree Tullos, PhD, PE (OR)

Professor, Water Resources Engineering

Oregon State University

Julie Alexander, PhD

Assistant Professor (Senior Research)

Oregon State University, Department of Microbiology

Laurel Genzoli, PhD

Postdoctoral scholar

University of Nevada

Kristine Alford

PhD Student

Oregon State University

Issi Tang

MS Student

Oregon State University