Author: Chet Udell

Abstract:

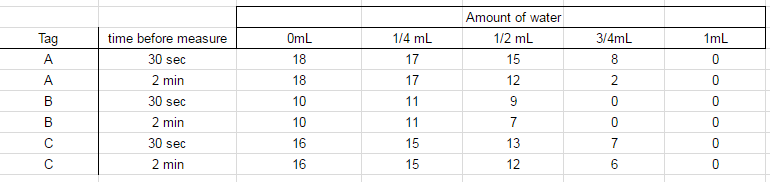

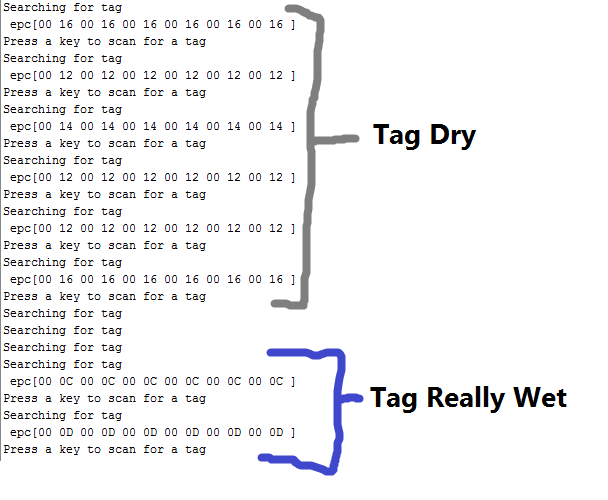

Our previous experiments have shown the RFID moisture sensor tags are in-fact reading gradual changes in soil moisture content. The next step is to compare the performance, consistency, and resolution of these tags to industry standard equipment to see how it measures up using Decagon Devices soil moisture sensors. In this post, Chet gets a 5TM Soil Moisture and Temperature Sensor chatting directly with an Arduino to deploy in experiments, and eventually integrate into the battery of available Internet of Ag sensors.

Objective:

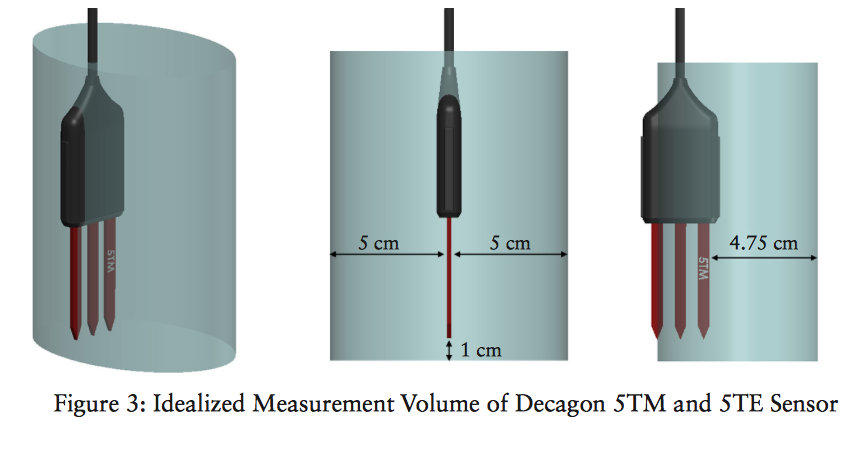

In order to compare the performance, consistency, and resolution of the RFID moisture tags, we hope to conduct some comparative experiments between these and Decagon’s popular soil moisture sensors, namely the 5TM (soil moisture + temp). Decagon’s readers can be pricey and we want to use these sensors in very specific ways, so the objective here is to get the sensors talking directly with an Arduino. The following method can be used to read any Decagon soil moisture sensor over the SDI-12 serial protocol. For more info on SDI-12, visit here. Why the 5TM? The 5TM determines volumetric water content (VWC) by measuring the dielectric constant of the soil (or other media) using capacitance/frequency domain technology. Signal filtering minimizes salinity and textural effects, making the 5TM accurate in most soils and soilless media. Factory calibrations are included for mineral soils, potting soils, rockwool, and perlite. – from http://www.decagon.com/en/soils/volumetric-water-content-sensors/5tm-vwc-temp/

Materials and Methods

What you’ll need:

- Download the above library, unzip. Rename the file “SDISerial” and place in the folder: <Arduinno root folder> / libraries

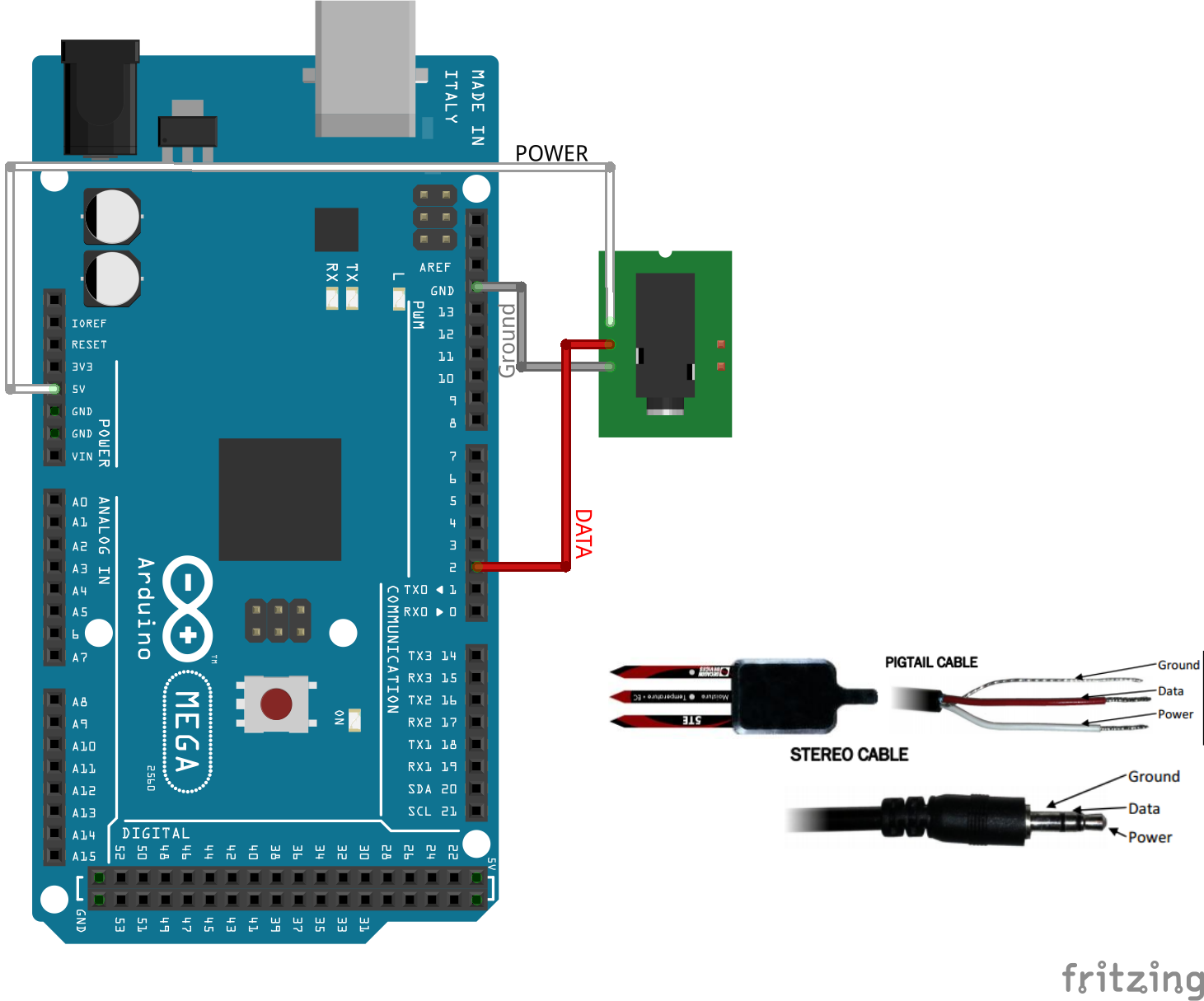

- Following the instructions on the library GitHub page (image included here), clip the 1/8 inch jack off of the Decagon sensor (ouch), strip off the leads to reveal a white, red, and “shield” wires. Solder each wire to a 0.1in pitch male header to use in a breadboard.

- Connect your arduino up to a breadboard and the 5TM lines White => 5V, Red => DATA_PIN, Shield => GND

- DATA_PIN MUST be connected to a pin with a hardware interrupt (for Uno, P2 or P3).

- Use the below code and you’ll get soil moisture and temp readings (in Celsius).

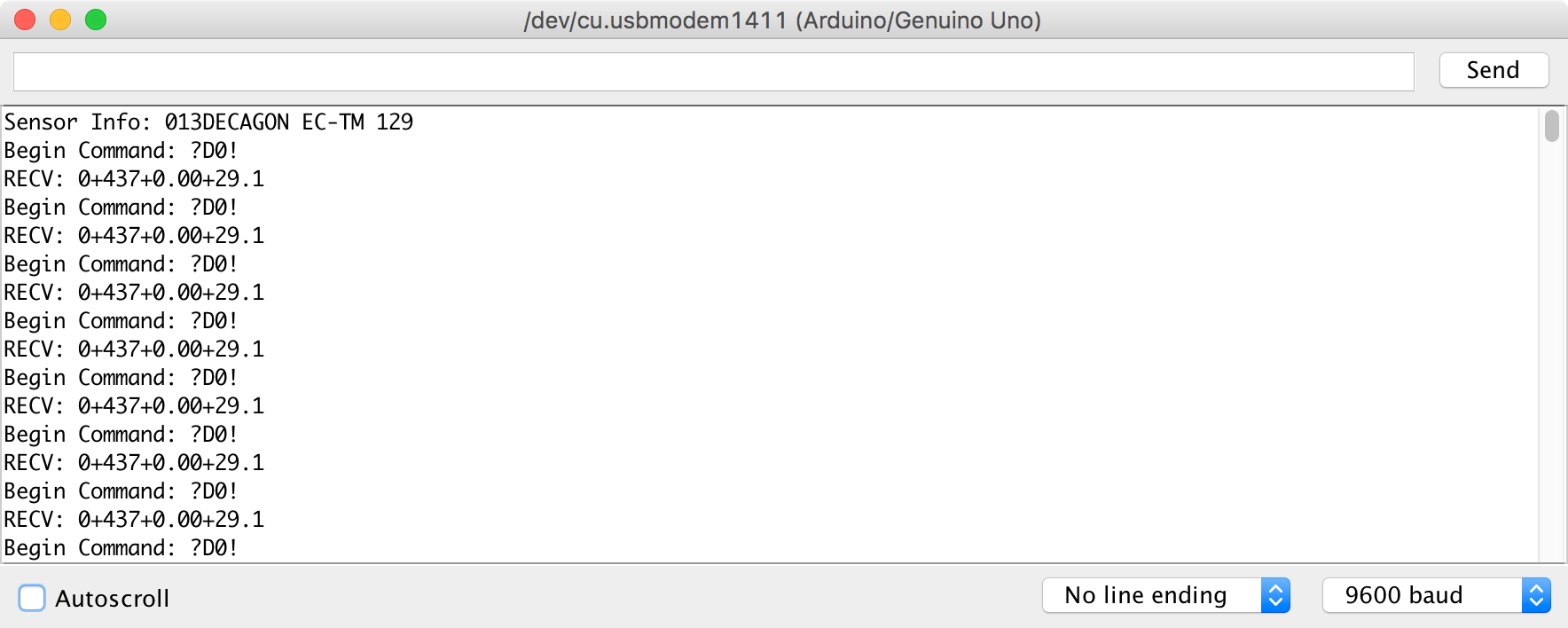

- Your output will look like the below screen print

Results

As you’ll see from the below code and printout, the SDISerial library enables the arduino to send commands to the 5TM to procure data. Now, we can employ these sensors in almost any Arduino application! This is done by creating an instance of SDISerial connection(DATA_PIN); and then starting the serial connection using connection.begin();

You can then use the function connection.sdi_query() to send various commands to the 5TM. This function uses 2 parameters: (command, timeout-duration)

connection.sdi_query(“?M!”,1000); This sends a message to query the first device on the bus – which in use seems to refresh the values of the sensor readings, but does not return the sensor reading itself. Instead, it returns a message that tells you the maximum wait before the measurement is ready. timeout set for one second.

connection.sdi_query(“?I!”,1000); will get sensor info and timeout if no response in 1 second

connection.sdi_query(“?D0!”,1000); will query the 5TM for sensor data

/*

Tested on UNO R3.

Sketch was built with Arduino 1.6.12

Dependency: Joran Beasley SDISerial Library

Accessed May 26, 2017 here:

https://github.com/joranbeasley/SDISerial

download and rename folder "SDISerial" and place in "<ARDUINO_ROOT>/libraries"

Tested with the with the 5TM Soil Moisture and Temp Sensor:

http://www.decagon.com/en/soils/volumetric-water-content-sensors/5tm-vwc-temp/

Hook-up:

the WHITE wire goed to 5V. however you could also connect it to a pin and drive power only when you wanted it

the RED wire is the DATA_PIN. - you must hook it up to a pin that can process interrupts (see link below)

the remaining "shield" wire must be connected to ground

*/

#include <SDISerial.h>

#include <string.h>

#define DATA_PIN 2

SDISerial connection(DATA_PIN);

char output_buffer[125]; // just for uart prints

char tmp_buffer[4];

char* resp; // Pointer to response char

//initialize variables

void setup(){

connection.begin();

Serial.begin(9600);//so we can print to standard uart

//small delay to let the sensor do its startup stuff

delay(3000);//3 seconds should be more than enough

char* sensor_info = connection.sdi_query("?I!",1000); // get sensor info

//print to uart

sprintf(output_buffer,"Sensor Info: %s",sensor_info?sensor_info:"No Response");

Serial.println(output_buffer);

}

//main loop

void loop(){

//print to uart

Serial.println("Begin Command: ?M!");

//send measurement query (M) to the first device on our bus

resp = connection.sdi_query("?M!",1000);//1 second timeout

//this really just returns a message that tells you the maximum wait before the measurement is ready

sprintf(output_buffer,"RECV: %s",resp?resp:"No Response Recieved!!");

Serial.println(output_buffer);

delay(1000);//sleep for 1 seconds before the next command

//print to uart

Serial.println("Begin Command: ?D0!");

resp = connection.sdi_query("?D0!",1000);//1 second timeout

sprintf(output_buffer,"RECV: %s",resp?resp:"No Response Recieved!!");

Serial.println(output_buffer);

delay(3000);//sleep for 10 seconds before the next read

}